Known Exoplanets

The modern exoplanet era began in 1992 when Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail discovered the first two exoplanets orbiting the pulsar PSR B1257+12 (Wolszczan & Frail, 1992). Just three years later, in 1995, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz detected 51 Pegasi b, the first exoplanet orbiting a Sun-like star (Mayor & Queloz, 1995). Both discoveries used indirect methods and revealed systems dramatically different from our Solar System.

Direct Imaging Techniques

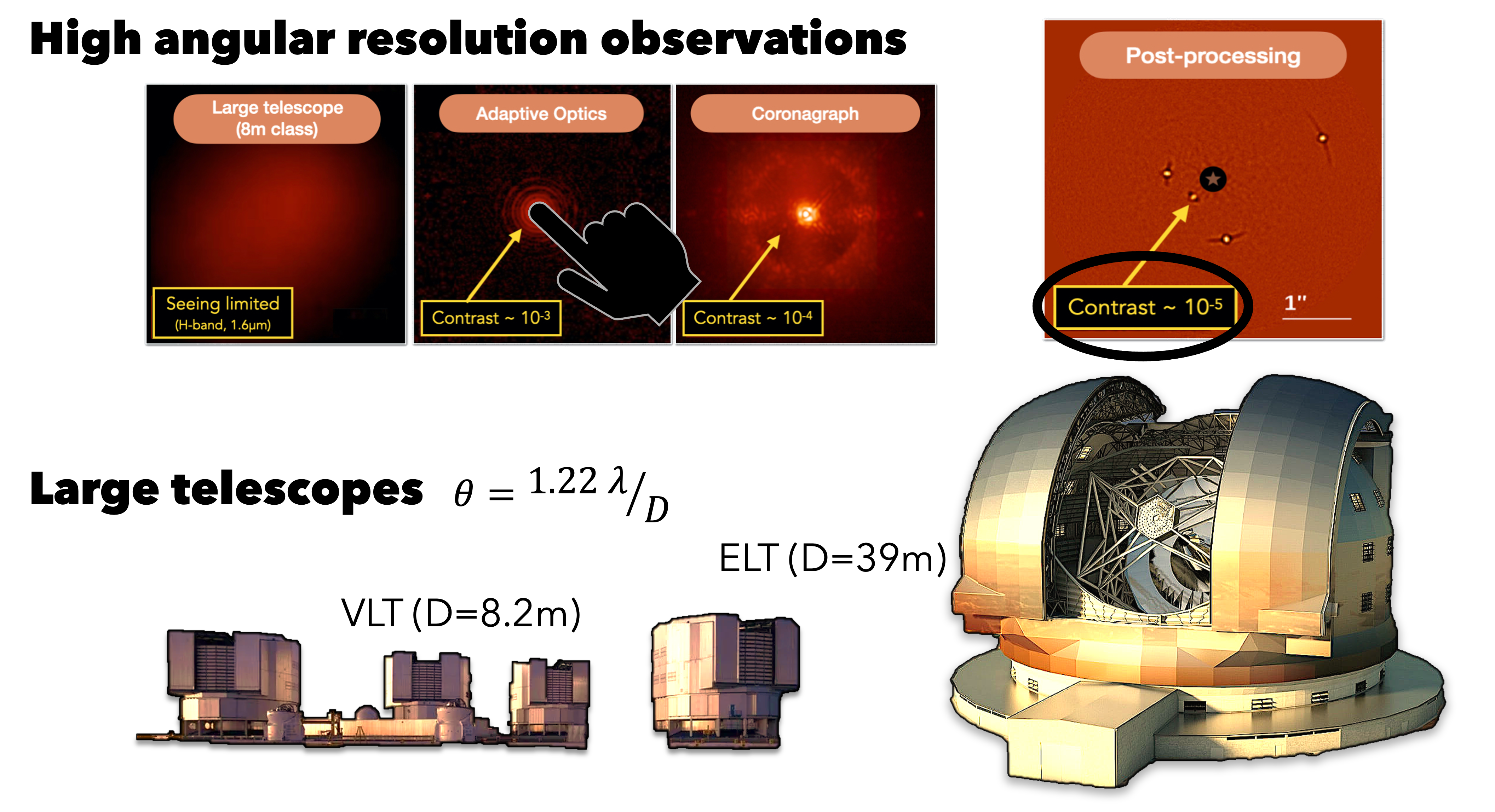

Direct imaging is extraordinarily challenging: host stars are orders of magnitude brighter than their planets, and planets orbit very close to their stars from our perspective. The angular resolution limit (θ ≈ 1.22 λ/D) means larger telescopes are essential for resolving smaller separations.

Modern observations combine three key technologies: Adaptive Optics (AO) corrects atmospheric turbulence to sharpen stellar point-spread functions (Babcock, 1953); coronagraphs physically block starlight to reduce diffraction (Lyot, 1939); and post-processing techniques (ADI, RDI, PCA) remove residual speckles (Follette, 2023). Together, these methods improve contrast by several orders of magnitude, enabling detection and spectroscopy of faint companions (see Figure above).

Direct imaging matured in 2004 with the first confirmed planetary-mass companion, 2M1207 (Chauvin et al., 2004). Since then, remarkable systems have been discovered: PDS 70, the youngest system where two planets have been imaged still in their formation environment (Keppler et al., 2018); HR 8799, a system with four imaged gas giants with well-constrained orbits (Marois et al., 2008; GRAVITY Collaboration et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2018); β Pic, a system with two planets within a debris disk (Lagrange et al., 2010, 2019); 51 Eridani b and AF Leporis b, the lowest-mass wide-orbit companions (Macintosh et al., 2015; Mesa et al., 2023; Franson et al., 2023); VHS 1256 b, the first exoplanet where silicate clouds were observed (Miles et al., 2023); and Eps Ind b, the coldest and oldest directly imaged exoplanet (Matthews et al., 2024).

Current Exoplanet Population

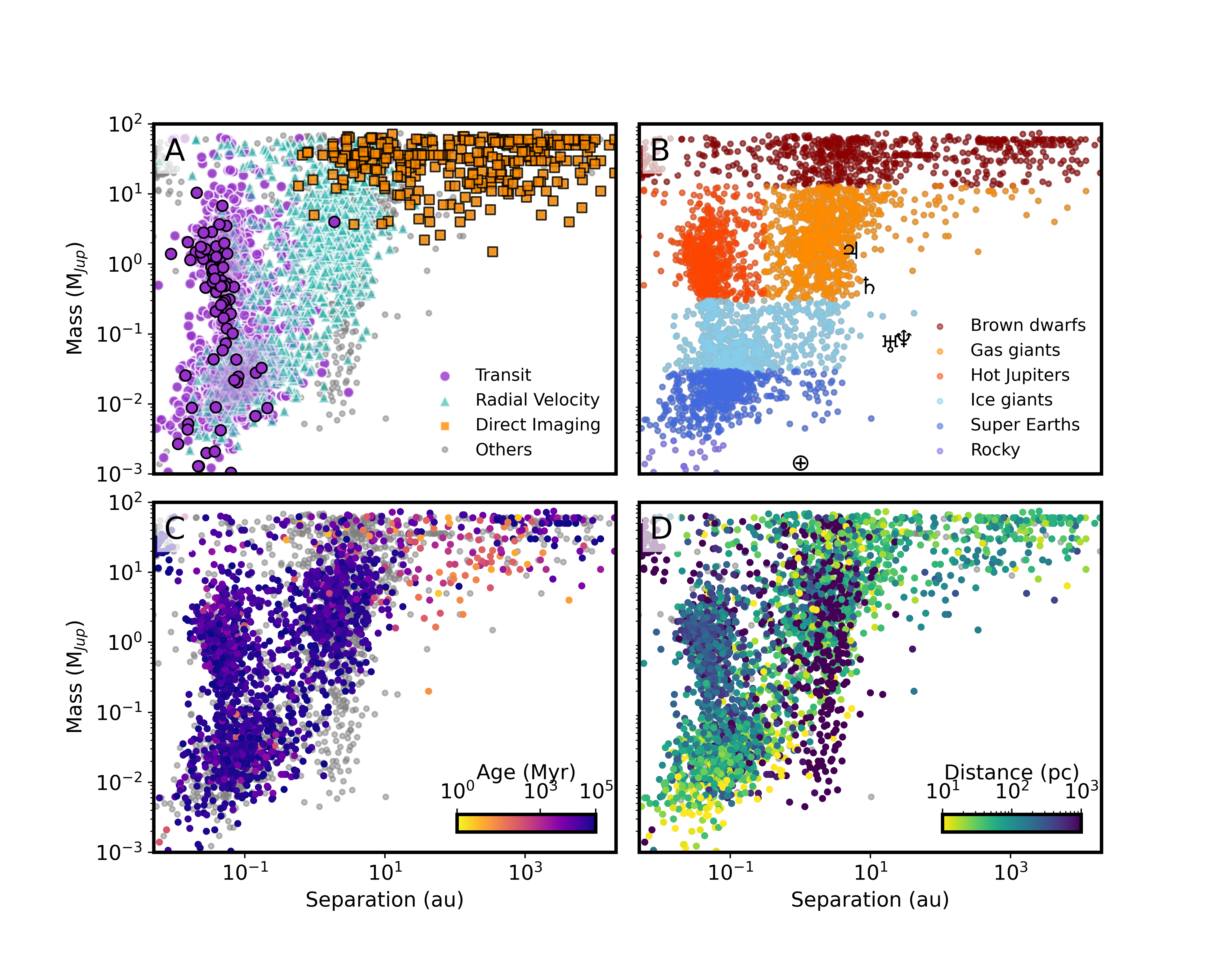

As of October 2024, over 7,300 exoplanets have been confirmed (exoplanet.eu catalog). Each detection method samples different regions of parameter space, as shown in the figure below: radial velocity and transits favor close-in planets, while direct imaging is sensitive to distant, massive planets. This creates observational biases, the absence of certain planet types in our data doesn't mean they don't exist, only that we lack the sensitivity to detect them.

Separation versus mass for the entire population of known exoplanets. Panel A shows observational techniques; Panel B shows planet types classified by mass and orbital distance; Panel C shows system ages; Panel D shows distances from Earth. (Credit: Data from exoplanet.eu catalog, Schneider, 1995–2024)

Spectroscopic Observations

Spectroscopy reveals atmospheric composition and physical properties. In Panel A of the figure above, all objects highlighted by a black border are those for which we have spectroscopic information, demonstrating the growing capability to characterize exoplanet atmospheres. Instruments use Integral Field Units (IFUs) or slits to capture spatial and spectral information simultaneously. Key facilities include VLT/SPHERE/IFS (Claudi et al., 2008), VLT/SINFONI (Eisenhauer et al., 2003), JWST/NIRSpec (Jakobsen et al., 2022), and JWST/MIRI (Rieke et al., 2015), each offering different trade-offs between wavelength coverage (near to mid-infrared), spectral resolution (low to high), and spatial information.

My research focuses on directly imaged exoplanets, using spectroscopy to study their atmospheres and constrain formation and evolution models. Direct imaging uniquely probes young, massive, widely separated objects, providing critical insights into planetary system diversity.